Many of us have been affected by the current events in Ukraine. As adults, we not only have to process these events ourselves but simultaneously figure out how to talk about it with the children in our lives. Children who have been directly affected by war will need psychological support far beyond the scope of this article. We wanted to focus on how to talk to children who have been exposed to war second-hand, for example via news, social media, family or peer connections.

In this situation, the first thing to remember is that kids are resilient. Most children who are exposed to war second-hand will be able to process this information without significant negative emotional impact. Having said that, when talking to children about a topic as difficult as war, adults should consider the child’s individual characteristics. In this article, we will examine how children understand the concept of war and discuss what to consider when talking to children about this difficult topic.

Cognitive Stages of Development

Stage 1: Birth- 2 Years

Children and adolescents go through periods of development that generally occur at particular ages. Piaget, a well-known psychologist who studied children’s cognitive development, delineated four main stages of ways in which children think and gather information. In the first stage, lasting from birth to around the age of two, infants and toddlers try to figure out what things are in the world by using their senses and engaging physically with the object. They are generally too young to be able to understand such abstract concepts as war and peace.

Stage 2: 2- 7 Years

In the next stage, lasting roughly from age two to seven, children begin to notice patterns and think in a slightly more complex way, but their thoughts typically still revolve around themselves and their own needs. Walker et al. (2003), in their study that used drawing as a tool to understand American children’s perception of war and peace, found that by the age of six, children partially understand the concept of war.

Stage 3: 7-11 Years

In the third stage, from about age seven to age eleven, children start to layer their thoughts and have the ability to think about more than one thing or person at a time. They create an order in their thinking and are increasingly able to express their thoughts in a way that makes more sense to the rest of the world. Walker et al. (2003) found that by the age of eight, children had a more complete understanding of war. At this age, their descriptions of war often included killing, fighting, soldiers, weapons, and dying.

Stage 4: 12+ Years

In the final stage, from the age of 12 and on, children start to understand hypothetical scenarios, which can help them plan more effectively and understand larger abstract ideas. With more experience and time, adolescents dive deeper into more challenging topics, looking at reasoning and strategies. They are increasingly able to grasp the complexity of war and engage in a more nuanced conversation about this topic.

In addition to their stage of development, the children’s level of connectedness to the situation way will influence the way they understand the concept of war. Some children have been directly affected by war; others have relatives who either live in a war-affected area or are serving in the military; yet others have witnessed it on the news or on social media. It is important to remember that even children who have not been directly affected by war still feel worried, sad, confused, angry and afraid by events that happen around the world.

Factors to Consider

Age and Developmental Level

There is not a one-size-fits-all approach to talking to kids about the war in Ukraine, but there are several factors to consider when preparing for this type of conversation. First, consider your child’s age, stage of cognitive development, and temperament. Younger children will need a heavily simplified version of the events, where you can focus on good people standing up against bullies, and avoid specific details of violence. By contrast, older children and adolescents may be able to handle a more detailed conversation about the geopolitical and historical significance of current events. Regardless of their age, children with a more sensitive temperament or children who are prone to anxiety may do better with a simplified version. Generally, it is better not to bring up these difficult topics right before bed, or when the child is tired or stressed.

Individual and Cultural Factors

Second, consider what the child’s frame of reference is for these particular events. Does the child have a family history that connects to a time of war? Do they practice any cultural or religious traditions that connect to the current events? Do they have any books or movies that depict violence or war? What is their personal experience with trauma, violence, loss, or displacement? You can use these experiences as anchors to explain the current situation.

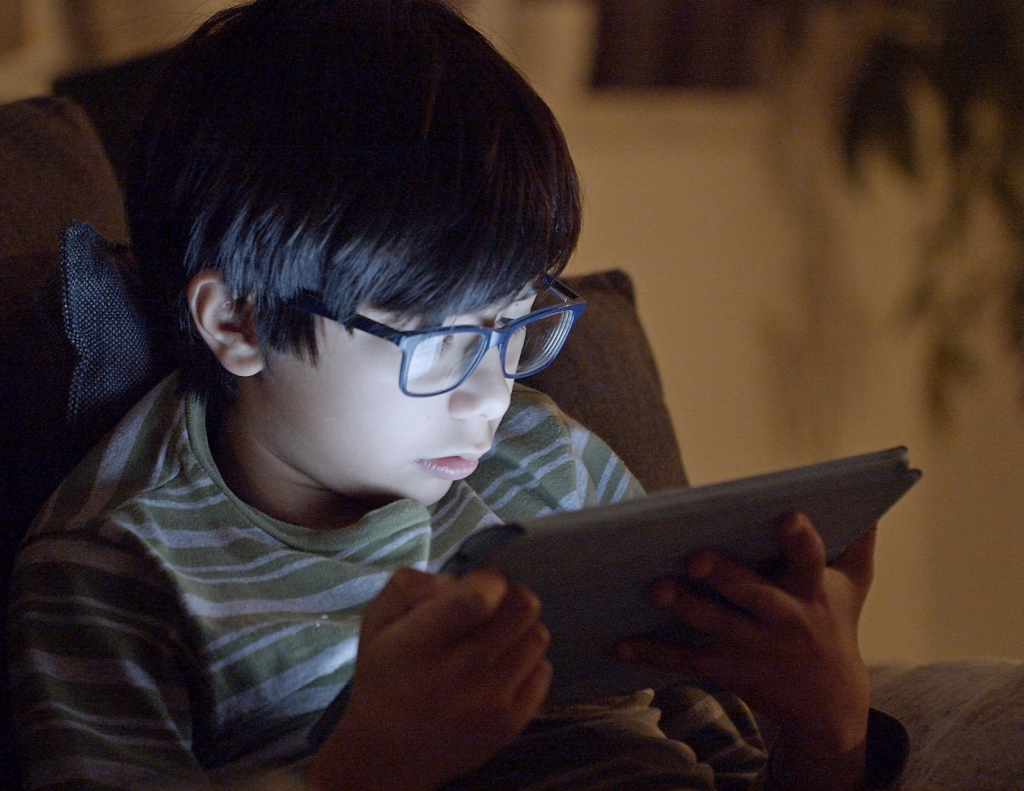

Exposure to War and Violence in the Media

Third, consider how much exposure your child has to images of violence or news, from either the TV or social media. In general, it is good for everyone to limit how much time they spend on these media outlets, but there isn’t a standard set limit due to the variability in the child’s age, emotional maturity, and other individual factors that only you as a parent may know. Nowadays, because of the way social media operates, some exposure is almost inevitable, even when a child is not seeking out information on the war. As adults, we have more awareness of how particular media impacts us, but kids are still working on developing this self-awareness. One way to foster this skill is to watch the news or videos together, so you can ask the child how they feel when watching and they can ask questions as they come up. You can also use this opportunity to discuss the trustworthiness of sources.

Tips to Keep in Mind

There are a few general tips to keep in mind when approaching a conversation with your child about war and violence. You can start out by asking them what their friends have been saying about the situation in Ukraine so that you can get an idea of what they already have heard. Try to avoid blanket statements or reassurances that could end up being false over time. Remind children that you are always here to talk and check back in with them even if they don’t bring the topic back up. Finally, remember that as a parent, you may also be feeling stressed, confused, and conflicted about the current events. The way we feel as adults may impact how the conversation goes. For suggestions on how adults can take care of themselves during these stressful times, check out the article written by my colleague, Dr. Inna Khazan.

Most people feel better if they feel that they can do something about a difficult situation. It may be helpful to end the conversation by talking about what children and adults can do to help those in need. Children can write letters or draw pictures for the people who have been affected by war and violence. Another option is to raise money and donate it to reputable organizations supporting Ukraine. Some children would prefer to attend events, such as a vigil, to feel a sense of community.

Even with positive action, things are not going to change overnight, and the situation will likely continue to be difficult for quite some time. It’s important to remind children that it’s not their job to make everything right and that there are adults who are working on it. As adults, we should be mindful of our children’s level of stress, increase the number of check-ins that you typically have with the child, and schedule more activities as a family away from screens, such as taking a walk, having a picnic or having a board game night.

As the parent, you know your child best and will be able to determine the most appropriate way to approach topics involving war and violence. Factors such as the child’s age, stage of cognitive development, and temperament can impact what the child is ready to comprehend, but can also vary with each child. Show curiosity about what your child has been exposed to at school or via social media, and be ready to discuss the topic with them as in-depth as they want to go. While we may not be able to guarantee the outcome of any armed conflict, we can reassure our children that we will be there for them during challenging and confusing times.

Resources

References

- American Psychological Association. (n.d.). Children in the heat of war. Monitor on Psychology. Retrieved May 25, 2022, from https://www.apa.org/monitor/sep01/childwar

- American Psychological Association. (n.d.). Talking to kids about the war in Ukraine. American Psychological Association. Retrieved May 25, 2022, from https://www.apa.org/news/apa/2022/children-teens-war-ukraine

- Holcombe, M. (2022, March 2). Yes, you should talk to your kids about Ukraine. psychologists explain how. CNN. Retrieved May 25, 2022, from https://www.cnn.com/2022/03/02/health/kids-anxiety-ukraine-wellness/index.html

- How to talk to your children about conflict and war. UNICEF Parenting. (n.d.). Retrieved May 25, 2022, from https://www.unicef.org/parenting/how-talk-your-children-about-conflict-and-war

- Thompson, P. (2019, August 15). 2.1 cognitive development: The theory of jean piaget. Foundations of Educational Technology. Retrieved May 25, 2022, from https://open.library.okstate.edu/foundationsofeducationaltechnology/chapter/2-cognitive-development-the-theory-of-jean-piaget/

- Walker, K., Myers-Bowman, K. S., & Myers-Walls, J. A. (2003). Understanding War, Visualizing peace: Children draw what they know. Art Therapy, 20(4), 191–200. https://doi.org/10.1080/07421656.2003.10129605 Wang, F. K.-H. (2022, March 10). Tips for helping young people cope with news about Ukraine and Russia. PBS. Retrieved May 25, 2022, from https://www.pbs.org/newshour/education/talking-to-your-children-sensitively-about-whats-going-on-in-ukraine

Acknowledgments

This blog post was prepared with the help of Becca Laudermilk, a second-year graduate student at Tufts University’s Eliot-Pearson Department of Child Study and Human Development, concentrating in Clinical-Developmental Health and Psychology. Becca loves working hands-on with children, having spent a lot of her time in various classrooms, most recently in the Eliot-Pearson Children’s School’s kindergarten and first-grade room. Her special interests include transracial adoption, the foster care system, children with special rights, impacts of culture, and experiences of trauma.