“I know my son wants to make friends, but when he plays with others, the kids complain that he is being bossy.”

“My daughter came home from school and told me that she has no one to play with during recess.”

“I think my middle-schooler doesn’t know how to begin a conversation. He’ll say ‘Hello’ to his peers and then look down at his shoes.”

These children, along with many others, likely have trouble navigating social interactions. They may have difficulty understanding other people’s point of view and recognizing how their behaviors impact the way others feel about them. Although some of these children have specific disabilities, such as autism spectrum disorder, many typically developing children also struggle with mastering age-appropriate social skills.

We used to think that social ability was a fixed trait, and that some people were naturally better at navigating social interactions than others. Thanks to the pioneering work by Michelle Garcia Winner and her colleagues, we now know that social skills can be learned with guidance and repeated practice. The process called Social Thinking (1) helps people realize that during their interactions they have the power to affect the thoughts and feelings of others. In this article, we will explore the concept of Social Thinking further.

What is Social Thinking?

According to Michelle Garcia Winner, Social Thinking is the method that individuals use to interpret the thoughts, beliefs, intentions, emotions, knowledge, and actions of another person in order to understand that person’s experience (1). We use social thinking in most aspects of daily life – when socializing with others, working on group assignments, thinking about characters in a novel, or playing team sports. Even when we are alone and thinking about other people, we use our social thinking skills!

The power of social thinking lies in the fact that it helps to resolve social challenges (2). Let’s think back to the example of a girl who has no one to play with at recess. Although many factors could be at play, it is possible that she has trouble with perspective taking. For example, when she initiates a game during recess, she may be unwilling to change her rules to accommodate other children, which will make it not enjoyable for others to join in. Another possibility is that she does not wait for her turn when using the slide or the swings. Or perhaps, when she loses a game of dodgeball, she cannot contain her frustration and calls the winning team hurtful names. These are all considered “unexpected” behaviors, which would make other children feel uncomfortable and less willing to invite her into their games (3). By using Social Thinking strategies, we can show this child how her actions affect others and help her change her behavior. This, in turn, will make it easier for her to develop and maintain friendships.

Perspective Taking Tools

One way to teach perspective taking is through four steps that put the child in another person’s position. In Step 1, the child looks at her surroundings to notice who is around her at that moment. In Step 2, she asks herself why the person is near her. Do they want to play a game with me? Do they look ready to start a conversation? In Step 3, the child considers what the other person thinks about her, and in Step 4, she monitors and modifies her own behavior (4). For example, if she notices that her peer is making eye contact and smiling, this may indicate that it’s a good time to start playing a game together. On the other hand, if the peer is slouching and frowning, asking how he is feeling may be a more appropriate response. In this way, using the Four Steps of Perspective Taking can help children explore what behaviors are expected in specific situations (4).

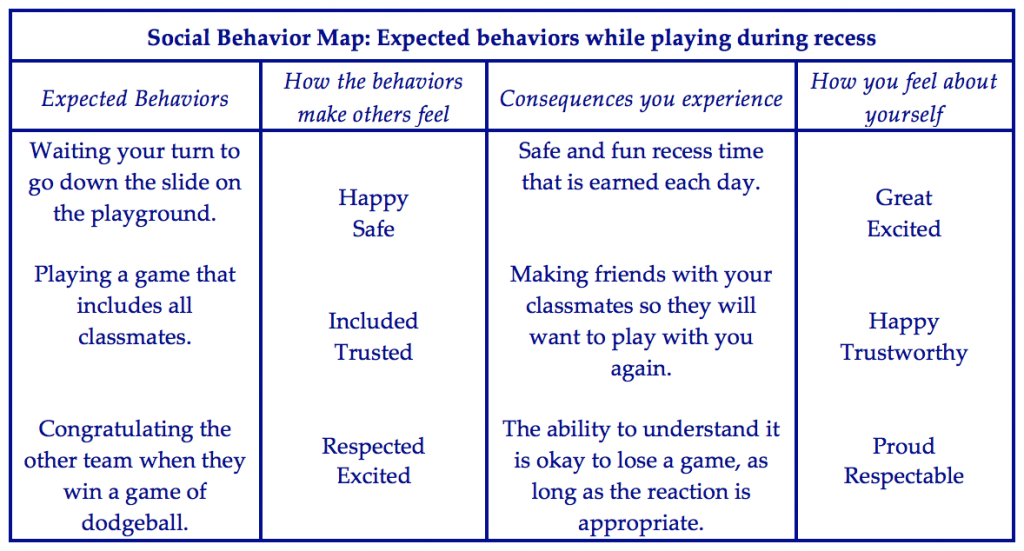

Another useful tool for teaching perspective taking is called Social Behavior Maps (SBM). SBM use a flow chart to teach children about the relationship between their own emotions and behaviors, and how their actions affect the emotions and behaviors of others. Social Thinking teaches children to be aware of their own emotions and then to predict the emotions of others based on their behaviors (3). The visual nature of the chart helps children understand what behaviors are “unexpected” or “expected” in a particular situation (3)(5). For example, the chart below refers to the earlier example of a child who expresses that she does not have any friends to play with at recess.

Although it may be trickier for some children than for others, all kids can learn to be social thinkers by keeping an open and flexible mind to new social situations (5). Understanding how to take another person’s perspective is a key component of developing and maintaining friendships. Through the development of perspective-taking skills, children can begin to understand which behaviors are expected, how to take the perspective of their classmates and peers, and to recognize emotions that impact their interactions. These skills will help children feel competent in social interactions, give them more opportunities to use their social skills, and provide experiences necessary to grow up feeling confident and included.

References

(1) Garcia Winner, M. Introduction to Social Thinking. Retrieved from https://www.socialthinking.com/Articles?name=Introduction%20to%20Social%20Thinking

(2) Garcia Winner, M. Social Thinking’s Mission. Retrieved from https://www.socialthinking.com/LandingPages/Mission

(3) Winner, M. G., Crooke, P., & Knopp, K. (2008). You are a social detective!: explaining social thinking to kids. San Jose, CA: Think Social Pub.

(4) Winner, M. G., & Crooke, P. (2011). Socially curious and curiously social: a social thinking guidebook for bright teens & young adults. San Jose, CA: Think Social Publishing

(5) Winner, M. G. (2003). Thinking about you, thinking about me: philosophy and strategies for facilitating the development of perspective taking for students with social cognitive deficits. London: Jessica Kingsley.

Acknowledgements

This article was prepared with the invaluable help of Jolie Straus, a second year graduate student at Tufts University’s Eliot-Pearson Department of Child Study and Human Development. Jolie desires to improve the lives of individuals affected by autism spectrum disorder and other neurodevelopmental and psychological challenges. In her future endeavors, she plans to work as a clinical psychologist and assist children and families through assessment, consultation, and treatment.